More hype about ‘three-parent embryos’ – but huge ethical and safety issues

Two consultations have been launched this week into what has been called the ‘three parent embryo’ technique for eradicating diseases caused by genetic mutations in the mitochondria of cells.

Both the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) and the Nuffield Council on Bioethics will be carrying out enquiries into whether it would be appropriate and ethical to use the new technique in developing new ‘therapies’ to prevent the birth or conception of children with mitochondrial disease.

The HFEA has been specifically commissioned to do so by the Secretary of State for Health together with the Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills.

At the same time scientists in Newcastle conducting basic research on the procedures have received £5.8 million, largely from the Welcome Institute, to determine the safety of the technique.

There has been a huge amount of media coverage on this over the last few days but for a quick overview of the science and ethical issues Nick Collins and Tom Chivers in the Telegraph are a good start. There is more helpful technical detail on the Nature News Blog.

The ‘three-parent IVF’ technique developed at Newcastle University (on which I have previously commented) can be carried out in two different ways.

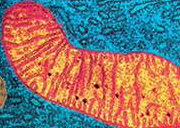

The first technique involves creating a fertilised egg in a laboratory, then removing its nucleus and placing it into another egg (from a third person) from which the nucleus has been removed (see picture above). This is called ‘pronuclear transfer’ and has already been used in Newcastle to create human embryos, some of which grew to the blastocyst stage (the stage when they would normally implant in the wall of the nucleus) before being destroyed.

In the second technique – Maternal spindle transfer (MST) – the nucleus of the mother’s egg is removed and placed into an enucleated egg from a woman donor before this new composite egg is fertilised. MST, where fertilisation takes place after rather than before nuclear transfer, was used in 2009 to produce two rhesus macaques (named Mito and Tracker) which were born healthy and developed normally.

Regardless of which of the two techniques is used, the resulting embryo has nuclear DNA from a man and a woman and cytoplasmic DNA (in the mitochondria) from a second woman – so effectively three genetic parents, although the contribution from the second woman is very small indeed (just 37 of 23,000 genes).

Researchers claim the technique could help prevent mothers passing on a rare inherited condition called mitochondrial disease to their children. Mitochondrial disease is unusual in that it is transmitted through DNA in the mitochondria (cell ‘batteries’) in the cell cytoplasm rather than through DNA in the cell nucleus.

Getting the regulatory changes necessary to allow using the technique to be used in patients now no longer involves parliament but only approval from the Health minister.

There are about 50 different known mitochondrial diseases which are passed on in genes coded by mitochondrial (as opposed to nuclear) DNA. They range hugely both in severity and clinical features. For most there is presently no cure and little other than supportive treatment.

We need to be clear in the first instance that this new ‘treatment’, even it were eventually to be shown to work (and there is considerable doubt about that), will do nothing for the thousands of people already suffering from mitochondrial disease or for those who will be born with it in the future.

It is primarily about trying to prevent people with MCD being born – or at least helping a very small number of mothers who carry the gene to have children who are unaffected.

And we need to remind ourselves that there are already some solutions available for those couples who find themselves in the tragic position of carrying genes for mitochondrial disease – including adoption and egg donation (although I have serious ethical reservations about the latter).

Tom Chivers sees little in the way of problems with the new technique but I have three big questions:

1.Will it work? I am very skeptical!

2.Is it ethical? No, there are huge ethical issues!

3.Is the debate being handled responsibly? No, there are huge vested interests involved!

I have a great sense of déjà vu here. There is always in this country huge media hype about supposed breakthroughs in biotechnology and the IVF industry – especially the Newcastle group – is very skilled in arousing media interest.

But we have been here before with human reproductive cloning (the Korean debacle), so-called therapeutic cloning for embryonic stem cell research (which has thus far failed to deliver) and animal hybrids (now a farcical footnote in history).

We saw the false dawn most clearly with animal human hybrids where the biotechnology industry, scientists, patient interest groups and science journalists on the UK nationals duped both the public and parliament into legalising and licensing animal human hybrid research to produce stem cells.

The Newcastle unit is a world leader in promising much and delivering little – but given the short attention span of the media and the gullibility of the public few people seem to realise, remember or care.

I have questions about the safety and ethics of both techniques are as follows:

Safety questions

1. What will be the effect on the embryos of the small amount of abnormal cytoplasm containing defective mitochondria that is still being transferred?

2. Will any of these embryos survive beyond blastocyst stage? (cloned human embryos and animal-human hybrids produced by similar ‘nuclear replacement’ technology haven’t)

3. If they do survive will the nucleus from one embryo function properly with the cytoplasm of another?

4. Will the progeny be normal or be suffering from defects that are in fact worse than mitochondrial disease itself? (we know that cloning by nuclear replacement is possible in frogs, difficult in mammals, hugely problematic in non-human primates and currently not possible in humans)

Of course none of these safety questions will be able to be answered without research on hundreds if not thousands of human embryos, all of which will be destroyed in the process, which brings us to the ethical questions.

Ethics questions

1. What about the hundreds of human embryos that have already been destroyed in this research and the many more that will be destroyed now? Does the hunt for ‘therapies’ that might prevent a small number of disabled children (with mitochondrial disease) being born justify the destruction of hundreds if not thousands of embryonic human lives?

2. What will be the psychological effect on any progeny of the fact that their DNA is derived from three separate ‘parents’? What issues of identity confusion will arise in any children with effectively three biological parents?

3. Should we be able to choose effectively not to allow the disabled children, who would have been otherwise born by natural means, to be born? Why should parental preference for a ‘normal child’ take precedence over an (equally valuable) disabled child? Cristina Odone argues that we should be concentrating on finding treatments for disabling conditions, not preventing those who suffer from them from being born or conceived.

4. Where will this selection end? Some mitochondrial diseases are much less serious than others. Once we have judged some disabled babies not worthy of being conceived, where do we draw the line, and who should draw it?

5. What are the financial and ideological vested interests in this work? The Newcastle scientists have a huge financial and research-based vested interests and getting the regulatory changes and research grants to continue and extend their work is dependent on them being able to sell their case to funders, the public and decision-makers. Hence their desire for attention-grabbing media headlines and press releases and heart grabbing (but highly extreme and unusual) human interest stories that are often selective about what facts they present.

What is currently happening in Newcastle may be legal in Britain – but it is illegal in almost every other Western country for good public safety and ethical reasons. Britain is regarded by many as a rogue state in all this.

So I’m not letting myself be carried away by the hype and spin. And I’m not holding my breath about the promises of therapies.

And as for ethics, one embryo destroyed in research or one disabled person excluded from being born so as not to burden others means for me that we have already crossed a crucial moral rubicon.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!