Ethical objections to embryo research can trigger genuine progress

An admission from scientists in the latest issue of the journal Nature, that production of three-parent embryos may not accomplish the stated goals, reminds me of a promise made by then Prime Minister Gordon Brown in 2008, one that most people have long forgotten.

An admission from scientists in the latest issue of the journal Nature, that production of three-parent embryos may not accomplish the stated goals, reminds me of a promise made by then Prime Minister Gordon Brown in 2008, one that most people have long forgotten.

In fact, I suspect that many MPs and a good number of scientists would prefer his promises were conveniently forgotten. Talking about the creation of animal-human hybrid embryos Brown said: ‘I also see the profound opportunity we have to save and transform millions of lives through this strand of medicine.’

He continued: ‘The doctors and scientists I speak to are committed to what they see as an inherently moral endeavour that can save and improve the lives of thousands and, over time, millions of people.’ (emphases added)

To be fair to Brown, he was responding to the promises of scientists, aided by the media, to make these claims, and perhaps one day hybrid embryos will be successfully created and will help with some research. But the promises that they will save millions were utterly farcical, both then and now.

His promises, however, reflected a tiresome but winning strategy, that human reproductive cloning, ‘three-parent baby’, and germline research have all followed: make claims that promise the moon and then (sadly) admit you were wrong, or that it will take a lot longer and perhaps not achieve what you originally promised, but only once you’ve achieved the legislation and research licenses that you want.

Many of us warned, to little avail, that three-parent embryo research has three major problems. It is unsafe, it is unnecessary and it is unethical.

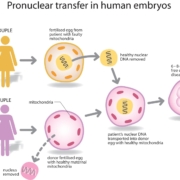

Briefly, to explain the research, in order to prevent a mother who has harmful mitochondrial mutations from passing them to her children, the proposed remedy is to transplant the nuclear DNA of her egg into another, donor egg that has healthy mitochondria (and which has been emptied of its own nucleus). The resulting embryo would carry the mitochondrial genes of the donor woman, and the nuclear DNA of its father and mother. Hence the term ‘three-parent embryos’.

The new research, by The New York Stem Cell Foundation (NYSCF), has discovered ‘potential adverse’ outcomes when using the technique in embryos. They found that in some trials, the transfer of unhealthy mitochondria could sometimes ‘carry-over’ and dominate the healthy mitochondria. The amount of carry-over mitochondria may increase over time, potentially causing one of the diseases the therapy was intended to cure, and therefore nullifying the technique’s effect.

This problem, the lead researcher says: ‘would defeat the purpose of doing mitochondrial replacement.’

Mary Herbert, a driver of the research at Newcastle University, admits that: ‘Levels of mutant mitochondria can fluctuate wildly in stem cells…They are peculiar cells, and they seem to be a law unto themselves.’

So it seems that the techniques used to create three-parent embryos are indeed unsafe (certainly for the foreseeable future) and highly unpredictable.

To go beyond researching embryos and to develop ‘treatments’ would require experimenting with the genetic make-up of babies and modifying the germline, which would impact future generations in ways we do not know and cannot predict. It would be both unsafe and unethical.

Last year, driven by the promise that it would save hundreds of lives, the UK government was the first (and only) country in the world to legalise this research, although the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority is yet to approve its use in a clinic.

Hence the great sense of déjà vu here.

Once again, we have had huge media hype about supposed breakthroughs in biotechnology, promising much but ultimately delivering little.

Perhaps one day there will be some progress with three-parent embryo research, but it will not fulfil the promises for treatments for hundreds of women, and it will not be able to shake off its ethical concerns.

All research needs ethical boundaries. Sometimes ethical objections can appear to be obstacles to innovation, but it sometimes happens that these ethical objections stimulate the imagination of researchers and finally lead to progress.

2012 Nobel prize winner, Shimya Yamanaka achieved great scientific advances within an ethical framework. The New York Times reported a few years ago, when he was doing embryo research himself: ‘He looked down the microscope at one of the human embryos stored at the clinic. The glimpse changed his scientific career.

“When I saw the embryo, I suddenly realised there was such a small difference between it and my daughters,” said Dr. Yamanaka, a father of two and a professor at the Institute for Integrated Cell-Material Sciences at Kyoto University. “I thought, we can’t keep destroying embryos for our research. There must be another way.”’

Yamanaka broke with conventional wisdom and after years of searching, he found an alternative to embryo research that took the research world by storm, and won him the Nobel prize.

So it is possible to achieve great scientific advances within an ethical framework.

Some of us are not surprised by the new research in Nature. That doesn’t lead to gloating but to hoping that both safety and ethical objections will stimulate the imagination of researchers to look for ethical alternatives that will finally lead to progress. Who could quarrel with that?

(First published on The Conservative Woman)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!