Claims that GM embryos will help boost IVF success rates are pure spin

Claims by the Times newspaper (and the BBC) that allowing GM embryos will ‘give a massive boost to IVF success rates’ are pure spin aimed at seducing regulators into giving a green light for highly controversial research.

Claims by the Times newspaper (and the BBC) that allowing GM embryos will ‘give a massive boost to IVF success rates’ are pure spin aimed at seducing regulators into giving a green light for highly controversial research.

Research scientist Dr Kathy Niakan, from the Francis Crick Institute in London, made her case last week to be the first in the UK to be allowed to genetically modify human embryos.

The regulator, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), considered her application last Thursday and will give a ruling later this month (Nature, Guardian, Mail, Telegraph). If approved the research could begin as early as March this year.

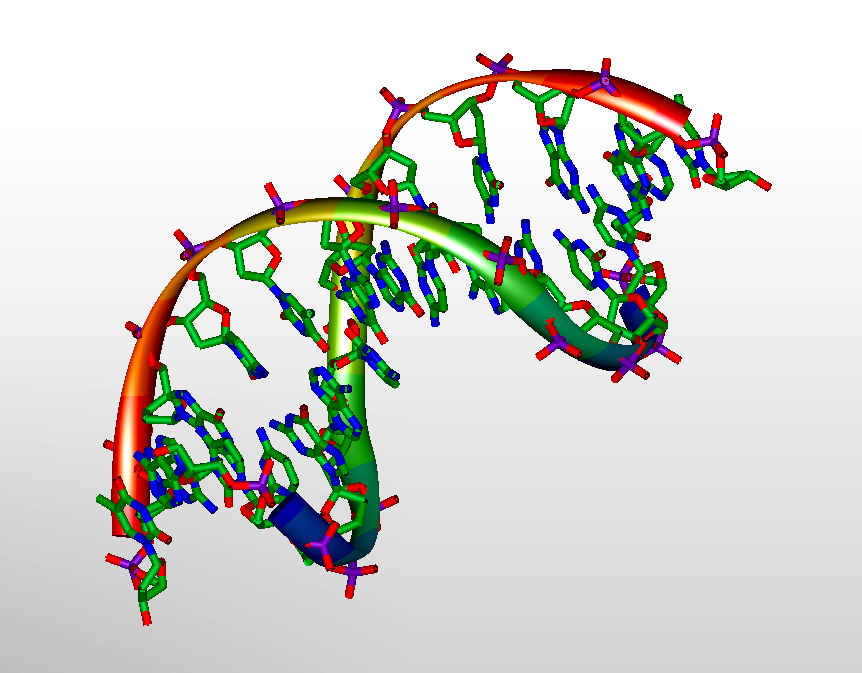

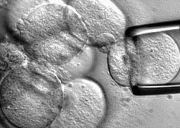

Niakan wants to use a new technique called Crispr-Cas9 to ‘edit’ genes in day-old human embryos left over from IVF in order to discover what role they play in normal embryo development.

She plans to start with a gene called Oct4, which is thought to have a critical role in embryo development, using 20-30 donated embryos. If this is successful she plans to move on to testing 3-4 other genes, each again using a further 20-30 embryos. No doubt further requests will follow once the principle has been established.

The research is highly controversial, and not just because it results in the destruction of the embryos being studied (each will be destroyed and examined at seven days).

International criticism is mainly driven by concerns about safety and unforeseen consequences – introducing genetic changes into a day old embryo will mean that any genetic change will be expressed in every cell of the developing human being, including reproductive cells (sperm and egg), and will therefore, if implantation follows, be passed on down the generations.

Although gene editing to treat some genetic disease in fully developed human beings appears to have huge early promise (such as in the case of Layla Richards who was saved from terminal leukaemia in London last year), gene editing in embryos (germline gene editing) has come in for huge criticism internationally and has so far only been attempted (unsuccessfully) in China.

Usually research like this needs to be conducted exhaustively using animals before it is attempted in humans. But Niakan argues that her research is necessary because ‘miscarriages and infertility are extremely common, but they’re not very well understood’ and that it ‘could really lead to improvements in infertility treatment’.

This claim, which has been propagated uncritically by the world’s media, is highly misleading, and lacking virtually any evidence base.

The fact is that we already have quite a good understanding of what causes IVF failure and miscarriage and it has very little to do with anything that can fixed by Crispr-Cas9.

The average implantation rate in IVF is about 25%. Inadequate uterine receptivity is responsible for approximately two-thirds of implantation failures, whereas the embryo itself is responsible for only one-third of these failures. The major reasons for embryo-related IVF failure and miscarriages are chromosomal abnormalities rather than problem with individual genes.

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (ACOG), most miscarriages (about 60%) occur when an embryo receives an abnormal number of chromosomes during fertilisation (see also here). This is called aneuploidy. This type of genetic condition may happen spontaneously or may be related to chromosomal abnormalities in egg and sperm (for example dislocations, deletions and inversions). It becomes more common in women of increased reproductive age.

Down syndrome is the best known form of aneuploidy and is caused by an additional 21st chromosome. In Edward’s syndrome and Patau’s syndrome (trisomy 18 and 13) it is chromosomes 18 and 13 respectively that are duplicated.

Babies with these conditions are often born alive but most other aneuploidies are lethal in utero – causing miscarriages or failed implantation. The commonest causes of miscarriages are trisomy 16 and 22. In a 2015 study of 832 early miscarriages, 368 (44.23%) were found to be abnormal. 84.24% (310/368) of these were aneuploidies. Trisomy 16 accounted for 121 of these 310 followed by trisomy 22, and X monosomy.

It may well be that trisomies of chromosomes other than 13, 18, 16, 21 and 22 (there are 23 chromosomes in each egg and sperm) prove lethal earlier in pregnancy or before implantation and so are less easily detected. It makes good sense and this would be a worthwhile area of further research.

But the key point to grasp here is that the genetic abnormalities which result in implantation failure (either in IVF or naturally) or miscarriage are chromosomal abnormalities, not abnormalities in single genes. But only abnormalities in single genes can be readily fixed with gene editing of the sort that the Crick Institute is proposing. Gene editing tools like Crispr-Cas9 do not fix chromosomal abnormalities.

However this simple fact has not been made clear to the media, to decision makers or the public. In fact researchers like Niakan, who must be aware of it, seem rather to have gone out of their way to fuel the misconception that gene editing will help IVF success rates.

This, it seems to me, is both negligent and disingenuous, as the key factor that is driving the call to approve this controversial new research is the supposed benefit to infertile couples.

In reality, it seems to be more about satisfying scientific curiosity about how genes work in the normal development of the human embryo with any therapeutic application a very distant dream.

British scientists have form in making wild and rash promises about new treatments in order to get approval for controversial research – the hype around animal-human hybrids and three parent embryos (mtDNA) are cases in point.

Few now will remember Prime Minister Gordon Brown’s empty promises in the Guardian on 18 May 2008 of animal-human hybrids (‘cybrids’) offering ‘a profound opportunity to save and transform millions of lives’ and his commitment to this research as ‘an inherently moral endeavour that can save and improve the lives of thousands and over time millions of people’.

That measure was supported in a heavily whipped vote by the then Labour government as part of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill, now the HFE Act, following a high-profile media campaign by the same science journalists and research scientists. But ‘cybrids’ are now a farcical footnote in history. They have not worked and investors have voted with their feet.

With respect to three parent embryos, David King, who runs the watchdog group Human Genetics Watch, remarked when the UK’s fertility agency, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), approved mtDNA work:

‘The decision is very disappointing, but comes as no surprise, since the HFEA can never say no to scientists. These experiments are scientifically useless and morally very problematic. The research lobby has distorted the scientific facts in order to defuse criticism.’

Gene editing, as I said at the beginning of this article, has great therapeutic promise for treating and perhaps even preventing some genetic disease. But gene editing of the embryo (germline editing) is extremely controversial and potentially very dangerous. Scientists around the world think that we are mad in Britain to be pursuing it.

At very least much more work is needed in animal models before we contemplate using it on human embryos; and in particular we need to establish first in animals whether or not it is likely to have any benefit at all in preventing infertility before we start making rash promises about IVF success rates in humans.

The case for gene editing in embryos needs to be based on real facts and evidence, not false hope, hype and misleading or frankly false claims from research scientists and their irresponsible press office portals (ie. the BBC and Times).

The British public and decision makers deserve to be treated with more respect than this.

Peddling misinformation like this will simply intensify suspicions held by many that research scientists, aided and abetted by their uncritical science journalist cronies, have something to hide or are trying to advance some personal financial or ideological agenda by deliberately pulling the wool.

The HFEA does not have a great track record in carefully scrutinising new scientific developments, but I hope that they will not easily capitulate in the face of Niakin’s specious claims about helping unfertile couples.

There might conceivably one day be a case for germline DNA editing. But this is not it.

A longer version of this article is available on the Christian Medical Comment Blog.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!